3. Tooth decay: understanding the process

The following section provides an overview of the physiological mechanisms behind tooth decay. For practical advice and family-friendly oral health tips, please refer to 'Section 4- Maintaining good oral health'

3.1 What is tooth decay

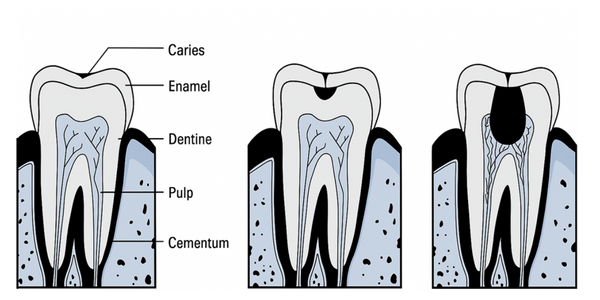

Tooth decay, the commonly used term for dental caries, is a common and chronic diet-related transmissible infectious disease, where bacterial by-products dissolve the tooth structure. The tooth decay process starts on the surface of the tooth and if left untreated will progress towards the pulp (area containing nerves and blood vessels), in the center of the tooth.

Early childhood caries (ECC) is the term given tooth decay that affects children aged five years and under, where one or more primary teeth are decayed. ECC is also known as baby bottle tooth decay, nursing caries, or infant feeding caries. Deacy can begin as soon as the first tooth erupts.

The enamel layer on deciduous teeth is thinner than on permanent teeth, leaving deciduous teeth more susceptible to dental caries than permanent teeth. Whilst any tooth can be affected by tooth decay, the upper incisors are often more severely affected because of their early eruption. Conversely, the lower incisors often remain unaffected, as they are protected by the tongue, and bathed in fresh saliva released from the nearby mandibular salivary gland ducts.

Learn about identifying dental decay in 'Section 5.2 -Mouth checks: Key areas to observe'

3.2 The tooth decay process

The tooth decay process begins when bacteria in plaque feed on dietary sugars, producing acids and lowering the mouth’s pH . The lower pH in the mouth results in tooth minerals dissolving out of the tooth surface (demineralisation). When this happens repeatedly over time, the integrity of the tooth surface is weakened and can eventually break down..

As minerals are lost from the tooth surface, the texture and appearance of the surface changes, resulting in what we call a "white spot lesion". This is a sign of early tooth decay.

As more minerals are lost, the surface breaks down even further, resulting in a hole. This is why dental decay is commonly known as a "hole in a tooth".

For tooth decay to develop, the following four factors are required:

Immediately after cleaning teeth, a thin organic film forms on the teeth, which is quickly colonised by bacteria. The bacteria and film are called dental plaque. Plaque bacteria feed on fermentable carbohydrates (sugars) left on the tooth surface, producing acids that attack tooth enamel and contribute to demineralisation.

Fermentable carbohydrates are simple sugars and starches, such as glucose, sucrose, fructose, and maltose. These are metabolised by plaque bacteria, with acid produced as a by-product. The easiest way to avoid excess fermentable carbohydrates is by limiting fermentable carbohydrate exposure.

Refer to 'Section 4.4 Tooth friendly snacks and nutrition' for more about this topic

While any tooth surface can be decayed, susceptibility is largely influenced by enamel thickness and quality. Deciduous teeth, with their thinner enamel, are particularly vulnerable to decay. Areas that are difficult to clean, such as deep grooves or contact points between teeth, also increase susceptibility. Conversely, teeth that have been strengthened with fluoride are less prone to caries.

The risk of tooth decay increases with prolonged and repeated exposure to decay-promoting factors over time. This cumulative effect is influenced by variables such as position and closeness of one tooth to another, ease and regularity of cleaning, and the length of time the teeth have been in the mouth. New deciduous teeth, which have had limited exposure to fluoride, can develop caries rapidly if frequently exposed to sugars.

3.3 Demineralisation and Remineralisation

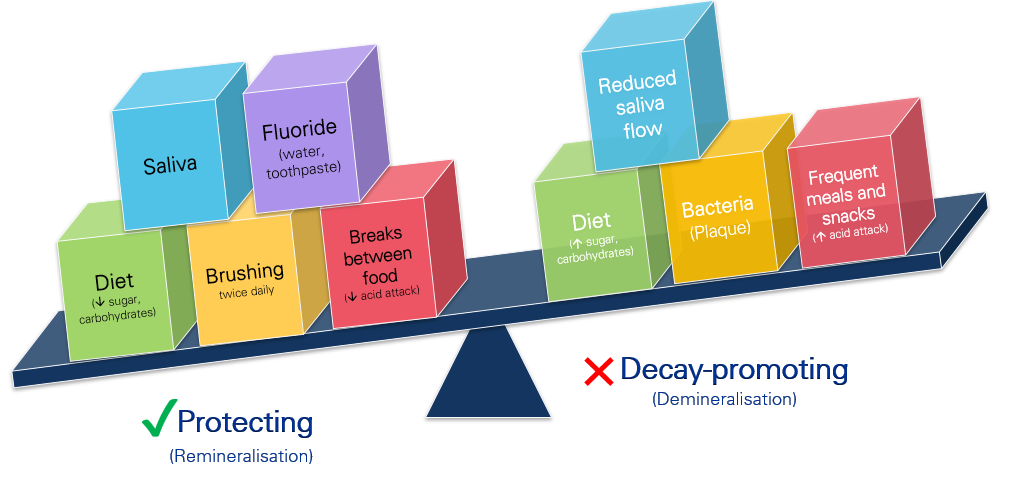

Demineralisation is the loss of minerals (including calcium) from the tooth enamel and remineralisation is when minerals are redeposited into the enamel. In a healthy oral environment, the demineralisation process is typically balanced by remineralisation. This dynamic process is influenced by factors such as saliva, fluoride, and diet. Maintaining this balance is crucial for preventing tooth decay.

A balancing act

Managing dental health involves balancing protective (remineralising) and decay-promoting (demineralising) factors.

3.4 Factors which protect against tooth decay

Factors that contribute towards remineralisation of the tooth surface and help to protect against tooth decay include:

Effective oral hygiene , including twice-daily brushing with fluoride toothpaste (over 18 months of age), is vital for reducing plaque accumulation. Regular dental check-ups are also essential for early detection and prevention of decay.

Fluoride acts as a repair kit for teeth. Following an acid attack, the fluoride in saliva helps to drive remineralisation. A constant low-level supply of fluoride within the saliva is beneficial. When fluoride is incorporated into the developing tooth structure (such as drinking fluoridated tap water during early childhood and primary school years), the tooth structure is more stable and less likely to undergo demineralisation. It can be likened to placing steel reinforcement into concrete structures.

Refer to Section 8: Fluoride- Promoting population health for more about fluoride.

A diet low in fermentable carbohydrates and rich in essential nutrients, such as whole foods, fruits , and vegetables supports overall oral health. Foods containing calcium help strengthen enamel, and vitamin D is important for tooth formation

Refer to 'Section 4.4-Tooth friendly snacks and nutrition' for more on this topic.

Increasing the interval between consumption of fermentable carbohydrates (and the resulting pH drop resulting from bacterial acid production), allows the oral environment to recover from acid exposure and enables remineralisation to occur. Foods and drinks themselves may also impact the pH of the oral cavity. For example, soft drinks (including diet varieties) and fruit juice are acidic and will push the oral cavity into a low pH state.

Saliva plays a key role in protecting teeth and gums by neutralising acids (aiding in remineralisation) and washing away food particles and bacteria.

Saliva protects the teeth from tooth decay and performs several important functions, including:

- providing minerals necessary for the remineralisation of tooth enamel.

- acting as a buffer to neutralise acids (bring the mouth back to a neutral state).

- lubricating the mouth to assist food movement and speech.

- assisting formation of the pellicle, a protective barrier against bacterial plaque formed on the enamel by salivary proteins.

- Dehydration is the most common cause of reduced salivary flow.

- Medications and certain diseases can also reduce the flow of saliva and increase the risk of tooth decay.

- Saliva production naturally decreases during sleep, therefore the risk of damage is greater at night. This is one of the reasons that babies should not go to bed with a bottle, (and why children should only consume water after brushing their teeth at night) as there is less saliva to wash away any residual sugars and protect the teeth.

It is important to note:

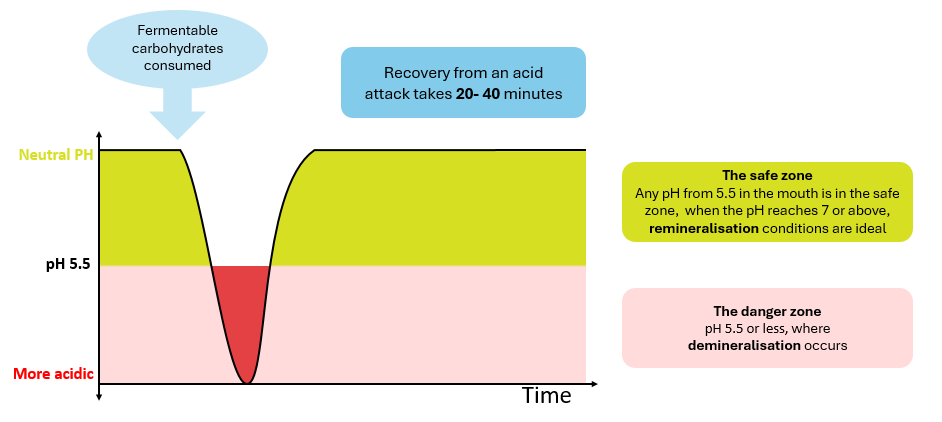

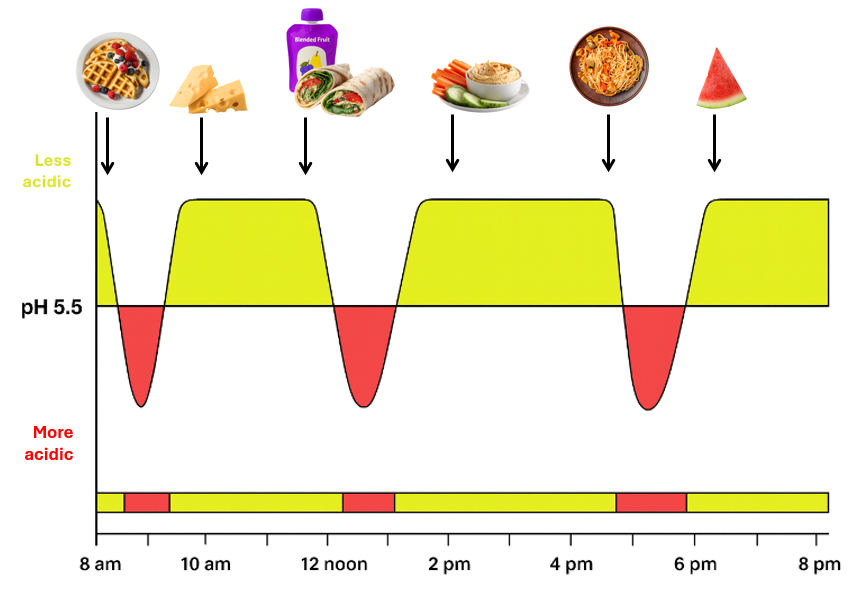

3.5 Frequency of snacking and exposure to sugars: The Stephan Curve

The Stephan Curve is a simplified graphic representation of the effects of consuming fermentable carbohydrates on oral pH over a given time period. It illustrates how the frequency of snacking and the duration of exposure to sugary foods and drinks can significantly influence oral health.

Each time fermentable carbohydrates are consumed, bacteria in dental plaque metabolise these sugars, producing acids that lower the oral pH. When the pH drops below the critical threshold of 5.5, enamel begins to demineralise, increasing the risk of tooth decay. If no other fermentable carbohydrates are consumed, the saliva is able to neutralise the acids and return the oral pH to neutral. Once the pH is above 5.5 again, the enamel can begin to remineralise.

An example of the Stephan Curve on a day eating tooth friendly foods:

On a day where the diet is well balanced, a child can enjoy three structured meals alongside tooth-friendly snacks, such as fruits, vegetables, and dairy. Because this pattern has reasonable intervals between sugar exposure, the mouth is able to spend more time remineralising than demineralising. This reduces the risk of dental decay, and is better for oral health remineralisation, promoting a healthier oral environment.

*please note this graphic is simplified for teaching purposes and is not a representation of the exact pH you will find in the mouth after eating the pictured foods

What about fruit? Whole fruits eaten as part of a varied diet pose far less risk than frequent consumption of sugary drinks or sticky sweets. People don't tend to eat whole fruits in excess frequently. Fruits differ in their sugar and acidity levels, but their overall effect on dental health is minimal when consumed as part of a varied diet that contains food from all 5 food groups. For example, watermelon has a high pH and low sugar content, making it less likely to contribute to tooth decay. Other fruits, like apples and pears, may be slightly more acidic but also stimulate saliva flow, which helps neutralise acids and protect teeth. Even citrus fruits, which are more acidic, provide vitamin C that supports gum health.

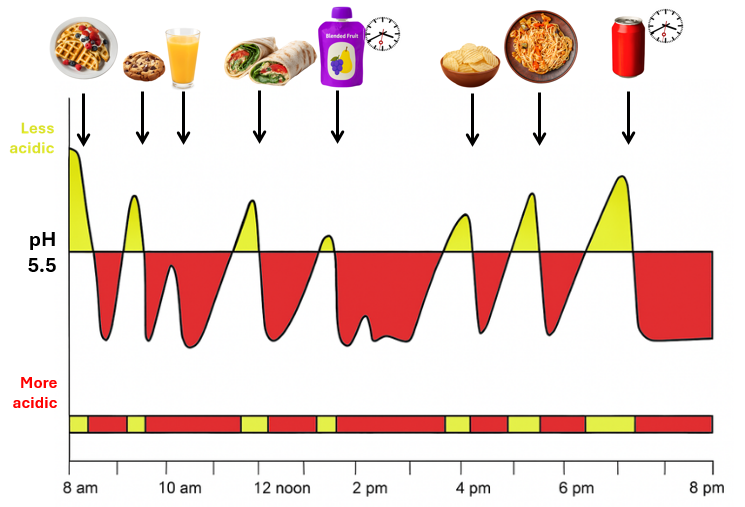

An example of the Stephan Curve on a day with frequent snacking:

In contrast, a day filled with frequent sugary snacks, such as biscuits or constant sipping of sugary drinks or fruit puree pouches, prolongs acid exposure. This continuous acid attack overwhelms the enamel’s natural ability to remineralise, significantly increases the time spent in a demineralisation-promoting state and therefore increases the risk of decay.

*please note this graphic is simplified for teaching purposes and is not a representation of the exact pH you will find in the mouth after eating the pictured foods

Frequent snacking results in: more time spent in the 'danger zone' (demineralising), less time spent recovering (remineralising).

Reducing the frequency and duration of sugary snacks supports healthier eating habits and improves oral health by giving the mouth time to recover from acid exposure. Refer to 'Section 4.4-Tooth friendly snacks and nutrition' for more on this topic