2. Oral anatomy, development, and habits in childhood

2.1 The mouth as part of the body

The mouth is a vital part of the body’s anatomy. For many people, it serves as the entry point for nutrition, air, and communication. Its structures are involved in processes such as chewing, swallowing, breathing, and speaking.

These processes are supported by a complex system of soft and hard tissues, including the maxilla and mandible bones, muscles, nerves and vascular bundles.

A healthy mouth is vital for overall health and wellbeing. Evidence increasingly links poor oral health to other conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and respiratory infections. Recognising the mouth as an important part of the body reinforces its role in overall health care and highlights the need to include oral health care in anticipatory guidance.

2.2 Structure and features of a healthy mouth

| Structures and features | Expected healthy characteristics |

|---|---|

Mucous membranes* * located on the lips, cheeks, palate, and underside of the tongue. |

|

| Teeth (if present) |

|

| Gums (gingiva) | Can range from pink and stippled to deeper hues with a brownish area along the gum line, depending on individual skin tones. They form a tight seal around the base of the teeth, acting as a protective barrier against bacteria and help anchor teeth to the jaw. |

| Tongue | Dorsal surface textured with visible papillae (small projections containing taste buds). Ventral surface: smooth with visible bluish veins |

| Palate (roof of the mouth) | Dome-shaped arch; includes the hard palate at anteriorly and the soft palate with a small uvula located posteriorly. |

| Saliva | Clear oral fluid that keeps the mouth moist - lubricates the oral tissues both soft and hard teeth. |

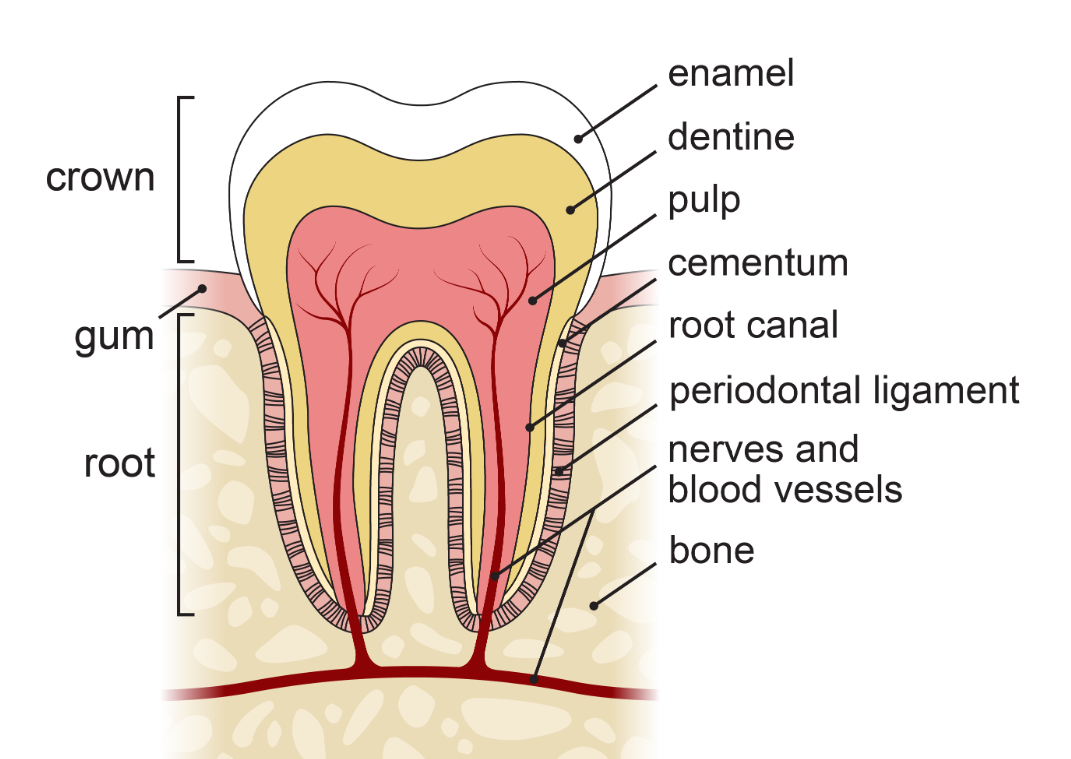

2.3 Tooth structure

Irrespective of tooth type, all teeth share the same basic structural features:

The crown is the visible part of the tooth that sits above the gum line (the line separating the gum from the exposed part of the tooth).

- covers the crown of the tooth

- hardest calcified tissue in the human body

- protective layer for the tooth and provides a strong surface for crushing and grinding

- thicker on the chewing surface and thinner near the gum line

- contains no nerve supply, therefore does not feel pain

Even though the enamel is very hard, it can be damaged due to:

- attrition (loss of tooth tissues and structure as a result of tooth-to-tooth contact e.g. tooth grinding)

- abrasion (loss of tooth tissues and structure wear of the tooth produced by something other than tooth-to-tooth contact, e.g. forceful brushing or using a toothbrush with hard bristles)

- erosion (loss of tooth tissues and structure wear of the tooth brought about by chemical process, e.g. dissolved by acid (i.e. reflux)

- fracture due to stress or trauma

- effects of dental decay or caries (this is caused by acid produced by a bacterial process in the regions of plaque accumulation/stagnation).

The root is the part of the tooth that sits below the gum line (and should not be visible).

The layer of tooth tissue under the enamel is the dentine. Dentine makes up the main portion of the tooth structure. In deciduous teeth, dentine is a yellowish in hue, while in permanent teeth it is lighter yellow. Dentine, while highly calcified, is softer than enamel and carries sensations such as temperature and pain to the pulp.

The pulp is the innermost portion of the tooth and is the only soft tissue of the tooth. It is made up of blood vessels, cellular substance, and nerves. It supplies nutrients to the tooth and its nerve endings transmit sensations such as pain and temperature to the nerves.

Cementum is a bone-like connective tissue that covers the root of the tooth. It is cream in colour. The cementum is a very thin layer covering the dentine. The dentine forms the bulk of the tissue within the tooth root. If the gum recedes from the tooth, then cementum is exposed, this cementum is easily worn away thus exposing the underlying dentine*.

*Patients feel a sharp sensation when brushing the teeth or eating cold or sweet food. This may be referred to as having ‘sensitive teeth’ and is usually an adult condition.

Cementum is also responsible for anchoring the periodontal ligament to the tooth which in turn anchors the tooth to the alveolar bone (jaw).

This can be described as the tissue ‘sling’ in which the tooth sits within the alveolar bone (jaw). The periodontal ligament is responsible for anchoring the tooth to the jaw. It is responsible for proprioception, recognising and absorbing the mechanical stressors of biting/chewing. It is also responsible for delivery of nutrients to the cementum and alveolar bone.

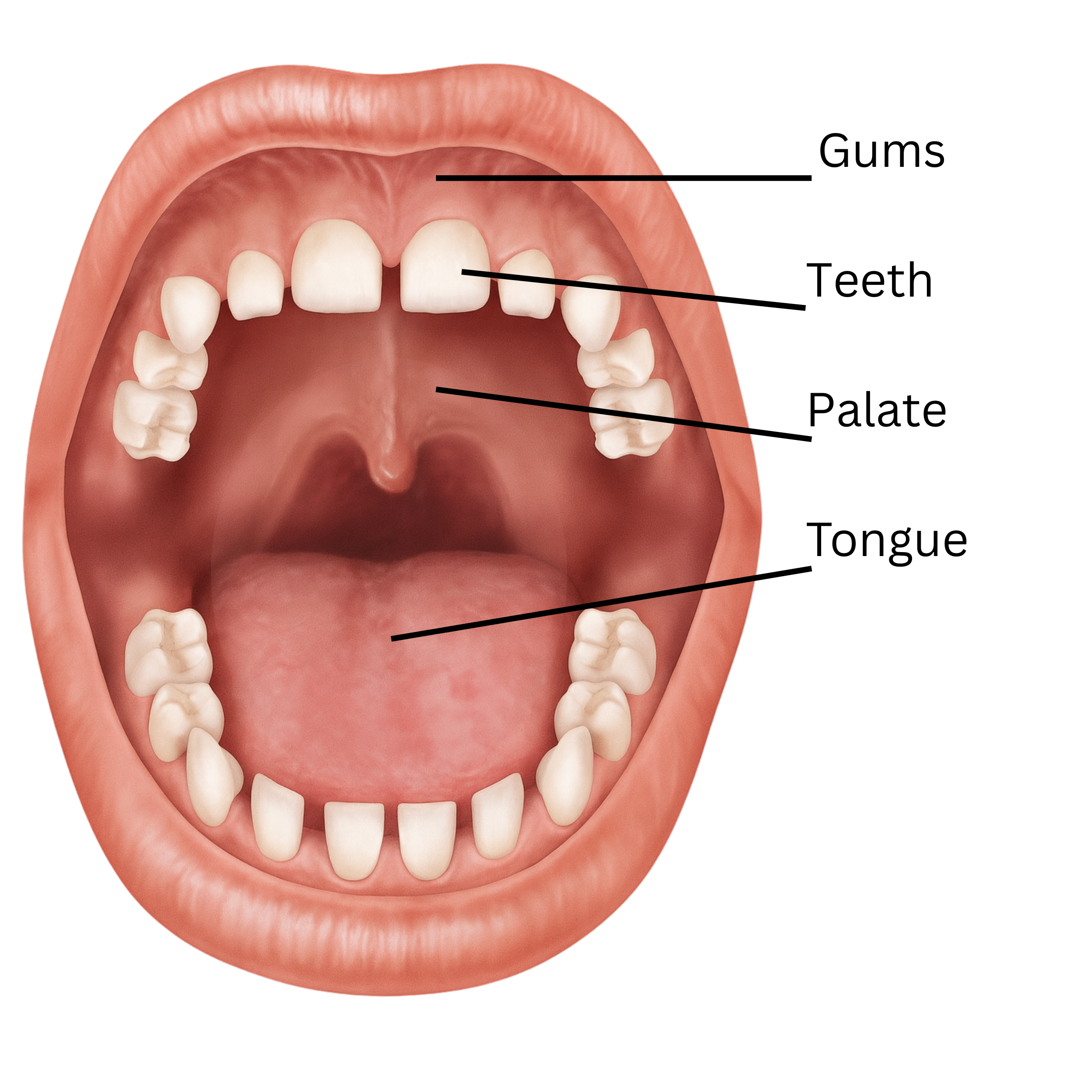

2.4 Types of teeth

There are four types of teeth

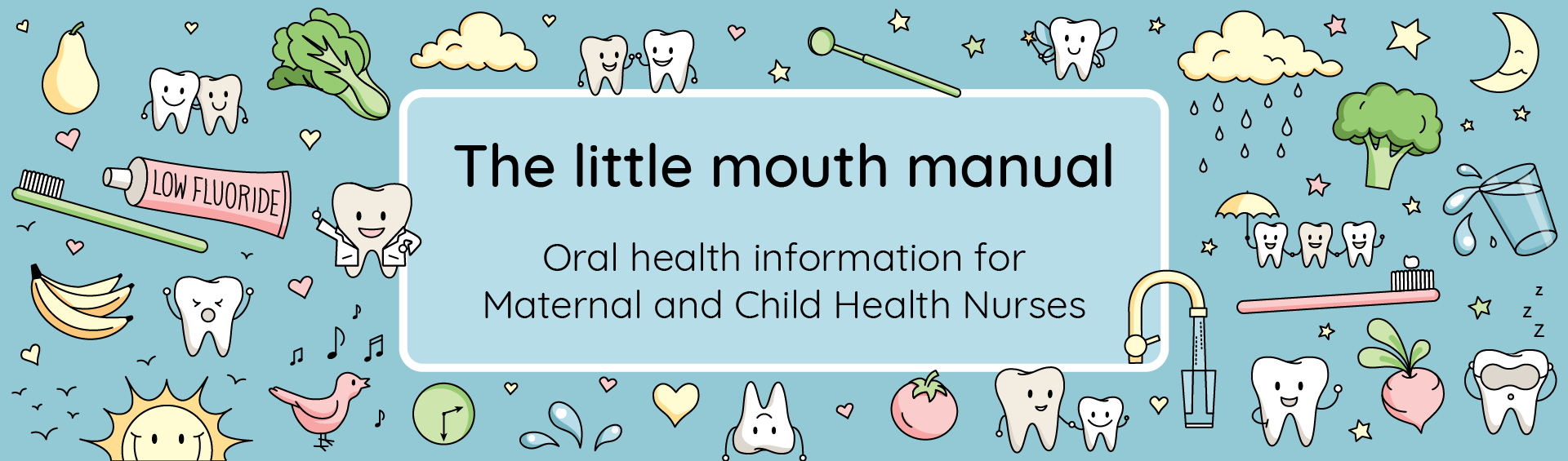

Incisors

|

|

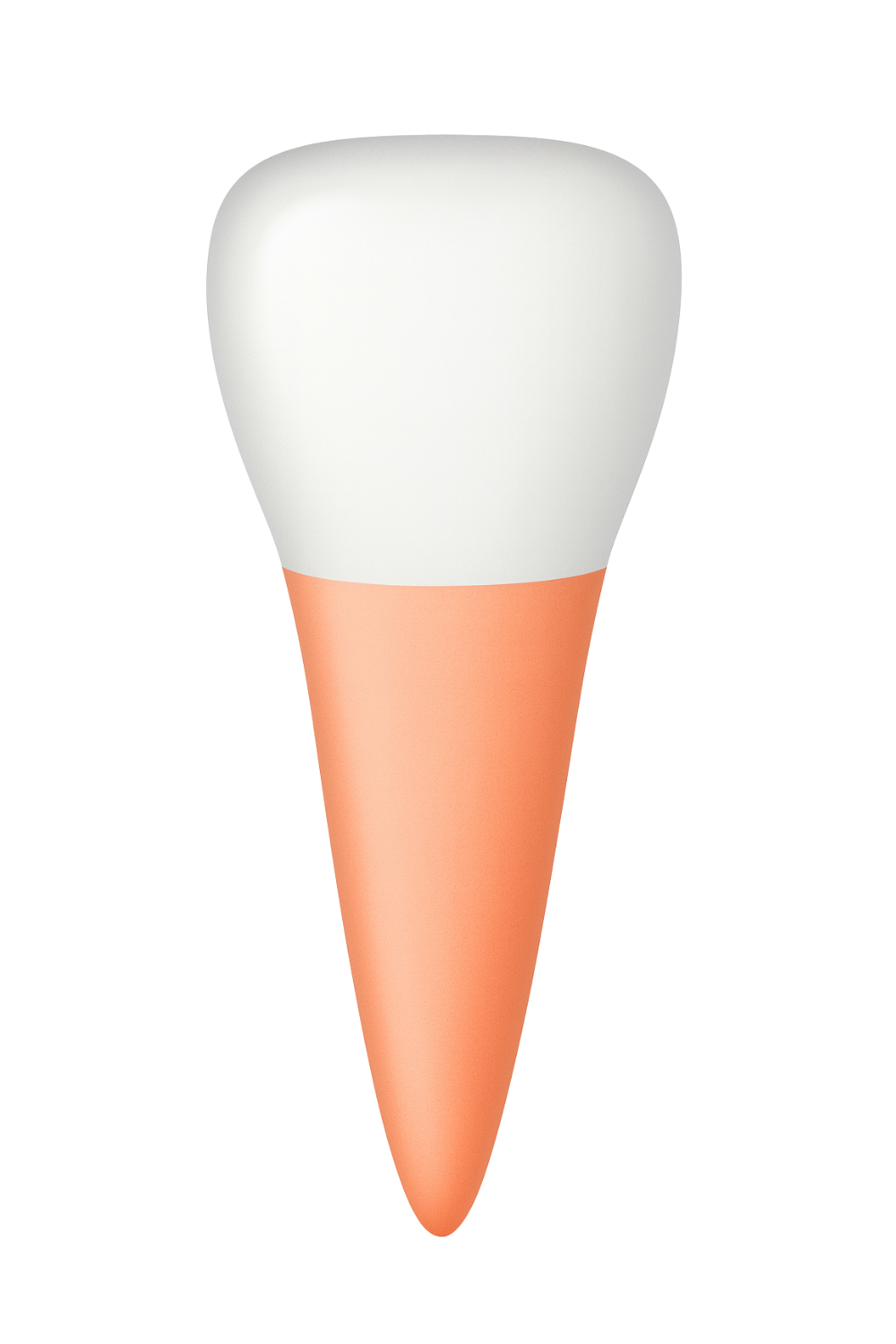

Canines

|

|

Premolars

only found in permanent dentition |

|

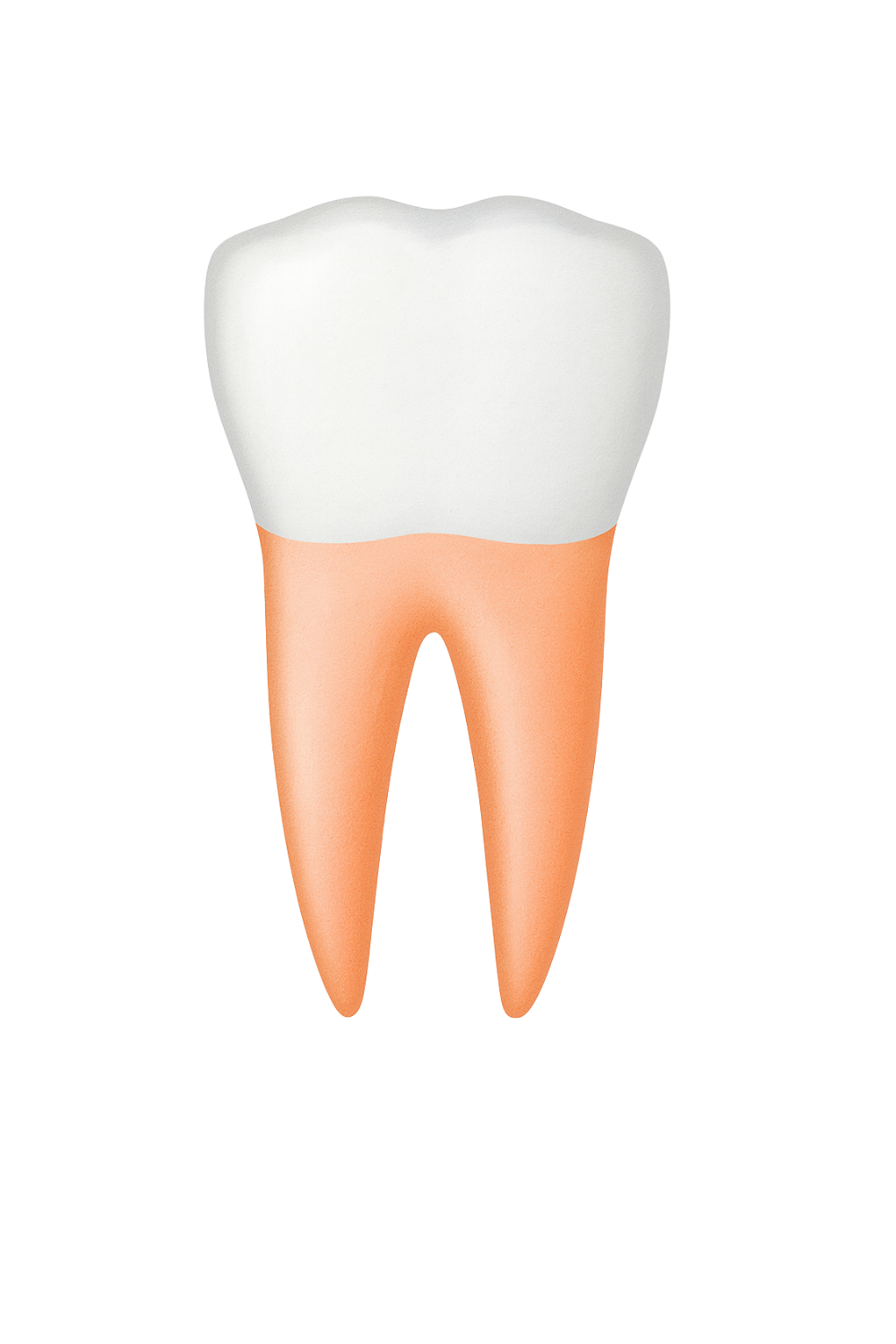

Molars

|

|

2.5 Tooth development in utero

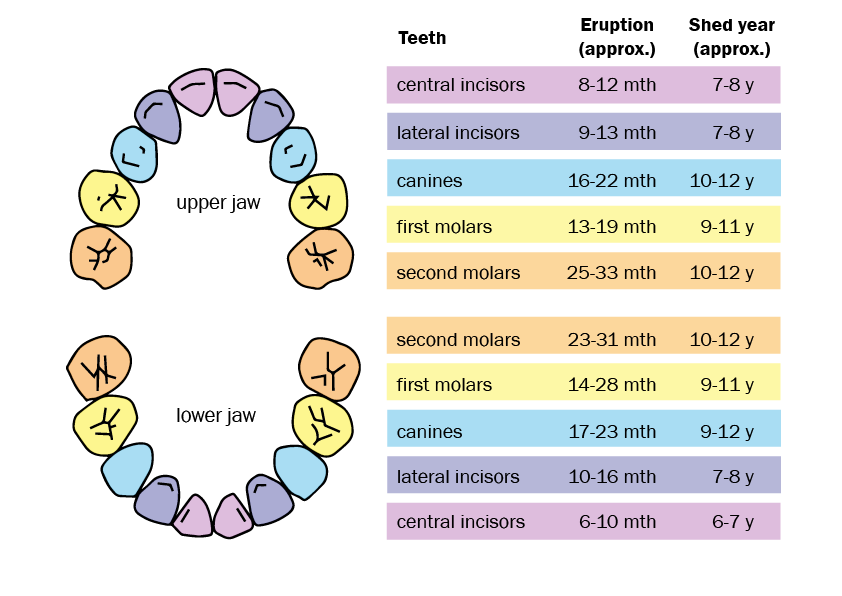

The formation of deciduous teeth begins after eight weeks in utero. The lower anterior (front) teeth are formed first, followed by the upper anterior teeth. The formation process continues after birth until the full set of twenty primary teeth; ten upper (maxillary) teeth and ten lower (mandibular) teeth have erupted. Eruption of the deciduous teeth usually begins when an infant is around six months old.

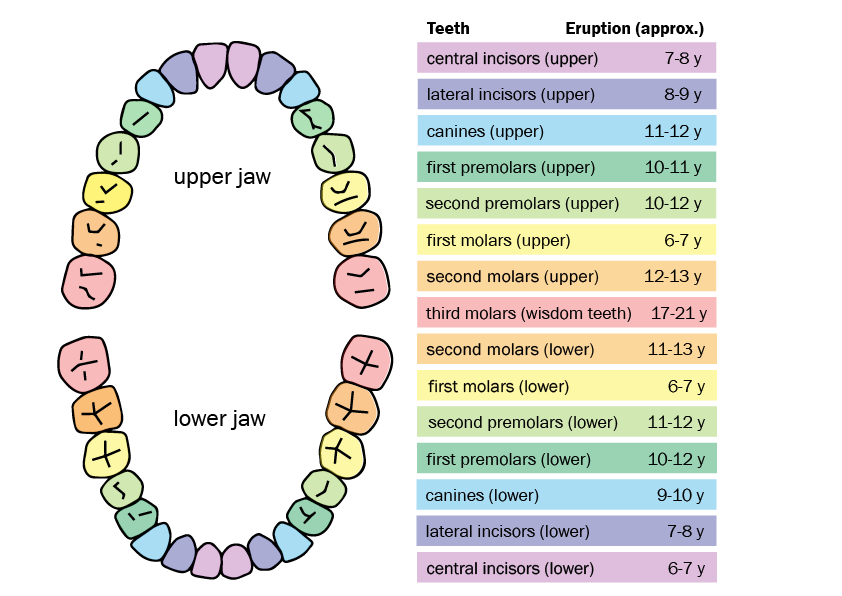

Permanent teeth begin forming during the 24th week in utero. The lower anterior teeth are formed first followed by the upper anterior teeth, the first permanent molars also begin to develop at this stage. The development continues after birth and throughout childhood until 16 upper (maxillary) teeth and 16 lower (mandibular) teeth have erupted. The permanent teeth begin to erupt when a child is around six years of age. Eruption continues until the upper and lower second molars come in between the ages of 11 and 13. If present, the third molars (wisdom teeth) may erupt as late as age 24, although some people never develop them at all.

The bud stage is the beginning of the development of each tooth. This starts with the formation of the dental lamina (a sheet of epithelial cells following the curves of the gums), which produces ten enlargements in each arch – these are the tooth buds. The tooth buds for the permanent teeth (which develop in a deeper part of the dental lamina) begin to form after 24 weeks in utero.

The bud stage is the beginning of the development of each tooth. This starts with the formation of the dental lamina (a sheet of epithelial cells following the curves of the gums), which produces ten enlargements in each arch – these are the tooth buds. The tooth buds for the permanent teeth (which develop in a deeper part of the dental lamina) begin to form after 24 weeks in utero.

During the cap stage the cells of the tooth grow and increase in number. The growth causes the tooth to bud  into a cap-like shape. During this stage, three primary structures begin to form, including the enamel organ (which forms the tooth’s enamel), dental papilla (forming the dentine and pulp) and the dental follicle (forming the cementum). These three structures work together in the development of a tooth.

into a cap-like shape. During this stage, three primary structures begin to form, including the enamel organ (which forms the tooth’s enamel), dental papilla (forming the dentine and pulp) and the dental follicle (forming the cementum). These three structures work together in the development of a tooth.

During the bell stage the cells differentiate and specialise, forming the various layers of the tooth. Enamel-forming cells, dentine-forming cells are created.

Enamel-forming cells, dentine-forming cells are created.

While the structures of the teeth are still developing, the surrounding area of the jaw also develops. Bone cells form the upper jaw (maxilla) and the lower jaw (mandible), and the shape of the future tooth crown is defined. The tooth crown is the part of the tooth that sits above the gum line - the part that you can see.

Bone cells form the upper jaw (maxilla) and the lower jaw (mandible), and the shape of the future tooth crown is defined. The tooth crown is the part of the tooth that sits above the gum line - the part that you can see.

During the final stages of tooth formation, the enamel and dentine cells increase in layers until the tooth is completely shaped. When the eruption of a tooth occurs, approximately two thirds of the root has formed. The tooth will be fully erupted for approximately two years before the full root length and thickness is attained. This is relevant to the permanent dentition. The primary or deciduous teeth complete their root formation a little faster.

completely shaped. When the eruption of a tooth occurs, approximately two thirds of the root has formed. The tooth will be fully erupted for approximately two years before the full root length and thickness is attained. This is relevant to the permanent dentition. The primary or deciduous teeth complete their root formation a little faster.

In the final stage of tooth development before eruption, the different layers making up the teeth calcify. Calcification is the hardening of the structure of the tooth by the deposit of calcium and other mineral salts. If a fully formed or partially developed tooth is damaged, it cannot repair itself like bone or skin. Damage at this point can have a great impact on the quality of the teeth.

Calcification is the hardening of the structure of the tooth by the deposit of calcium and other mineral salts. If a fully formed or partially developed tooth is damaged, it cannot repair itself like bone or skin. Damage at this point can have a great impact on the quality of the teeth.

2.6 Dentition across childhood

Dentition refers to the arrangement and types of teeth in the mouth. Humans will have two sets of teeth in their lifetime: first the deciduous, followed by the permanent teeth.

Deciduous teeth

Deciduous teeth are also known as baby teeth, milk teeth, primary teeth or first teeth. Deciduous teeth are whiter, smaller and softer than permanent teeth. Children will usually have their full set of 20 deciduous teeth by two and half to three years of age. Being smaller and softer makes them more prone to tooth decay and means diligence is needed with their care, diet, and hygiene. Whilst these teeth are replaced by the permanent dentition maintaining them is vitally important to the health and wellbeing of the child.

Healthy deciduous teeth are important for:

- efficient mastication of food – missing or decayed teeth may cause young children to reject foods that are difficult or painful to chew

- maintaining normal facial appearance

- formulating and developing clear speech patterns

- maintaining space for and guiding the eruption of the permanent teeth

- jaw development

- developing self-esteem.

Around the age of six years, the deciduous teeth begin to be replaced by permanent teeth. This process is known as exfoliation.

Developing good oral hygiene practices for the primary dentition not only helps to helps to safeguard the wellbeing of the child, but it also helps towards supporting the health and longevity of the permanent dentition

Permanent teeth

Permanent teeth, also known as second teeth or adult teeth, have a more yellowish colour compared to deciduous teeth. Permanent teeth are incredibly important (as are deciduous teeth) as they are designed to last a lifetime.

During primary school years, most children transition from a full set of deciduous teeth to a full set of permanent teeth. By around the age of 13, most children will have their full set of 28 permanent teeth, except for the third molars, or wisdom teeth, which may erupt later. At the stage when a child has both deciduous and permanent teeth, it is called the 'mixed dentition stage'.

Eruption of deciduous teeth

Although deciduous teeth begin to form in utero, they do not usually begin to erupt until a child is six to eight months of age. Eruption times vary from child to child, and there is a wide range of what is considered normal. Typically, a child will have a complete set of deciduous teeth by around two and a half to three years of age

In most cases no teeth are visible in the mouth at birth, although occasionally some babies are born with an erupted incisor tooth known as a natal tooth. Some babies might also develop a neonatal tooth, which is one that erupts within 30 days of birth (Cameron & Widmer, 2003).

Usually, teeth emerge in type and arch pairs, with the lower teeth appearing before the upper teeth. Girls often develop teeth earlier than boys. The ages provided are approximate, and children may have teeth erupt slightly earlier or later. As a rule of thumb, the sequence of tooth eruption is more important than the exact age, as some children may develop teeth at different times due to ethnic variations.

The upper arch (maxilla) and the lower arch (mandible) both have ten deciduous teeth:

- two central incisors

- two lateral incisors

- two canines

- two first molars

- two second molars .

Tooth exfoliation

Tooth exfoliation is the natural process by which the deciduous teeth become loose and are shed from the mouth, to be replaced by permanent teeth.

Unerupted permanent teeth develop in the jaws beneath the deciduous teeth. As the permanent tooth crown finishes forming and eruptive movement begins, the root of the deciduous tooth begins to resorb (dissolve). When enough of the deciduous tooth root has dissolved, the remaining part of the tooth can no longer be held by the jaw bone and the tooth becomes loose and ‘falls out’. The ‘replacement’ permanent tooth may already be seen in the space vacated by the primary tooth. It can take up to 6 months for the permanent tooth to fully erupt through the gumline post exfoliation of the deciduous tooth.

The following radiograph is an image which shows the upper and lower jaws of a child with a dental age of about four and half years.

All their primary teeth are present in their mouth, and the permanent teeth are in varying stages of development. Even though the crowns of the permanent molars have fully developed the teeth are not ready to emerge into the mouth. This will occur when approximately two thirds of the root structures have developed.

Description: Radiograph of a 4-year-old child with normal oral anatomy, showing a complete set of primary teeth, prior to the eruption of permanent teeth. Source: Radiopaedia.org

Description: Radiograph of a 4-year-old child with normal oral anatomy, showing a complete set of primary teeth, prior to the eruption of permanent teeth. Source: Radiopaedia.org

Eruption of permanent teeth

The upper arch (maxilla) and the lower arch (mandible) both have 16 permanent teeth:

- two central incisors

- two lateral incisors

- two canines

- four premolars

- six molars.

At about six years of age, the first permanent molars and lower permanent incisors begin to erupt.

Between the ages of approximately six and 12 years, children have a mixture of permanent and deciduous teeth (mixed dentition). By the age of 13, most children have all their permanent teeth except for the third molars (wisdom teeth).

Advice for parents when the permanent teeth are coming through

- Children can sometimes find that chewing is more difficult when teeth are loose or missing.

- Children should keep their toothbrushing routine. Extra care should be taken around loose teeth or sensitive areas.

- Loose teeth should be allowed to fall out on their own. If you try to pull out a tooth before it’s ready to fall out, it can snap, potentially causing pain and infection.

- Sometimes a permanent tooth will come through before the deciduous tooth has fallen out. If the deciduous tooth hasn’t fallen out within two or three months, the child should see a dental practitioner (Raising Children’s Network 2025).

- Carers may ask about mamelons, which are the three small bumps or ridges often seen on the biting edges of newly erupted permanent incisors. Mamelons usually wear down over time with normal chewing. They are rarely seen on deciduous teeth, as these ridges typically wear away during the teething process.

For advice for parents when deciduous teeth are coming through, see Section 2.8 -Teething

2.7 Nonstandard eruption patterns

Delayed eruption of the first teeth, or teeth appearing outside the usual sequence may be noticed by MCHNs, and is usually not a cause for concern. In rare cases, it may indicate an underlying condition/s.

- All children are encouraged to have their first dental visit by age one. All families not yet linked with a local dental service should be offered support to do so.

- If no teeth have erupted by age two, or if other teeth have erupted but the sequence is significantly varied (for example, no central incisors while other teeth are present), or if parents have expressed any concerns about tooth eruption, they should seek assessment and advice from a dental practitioner.

Both deciduous and permanent dentitions may have extra teeth, known as supernumerary teeth. Although these extra teeth usually don’t cause pain or immediate problems, they can lead to complications such as delayed eruption or crowding of the permanent teeth (Ata-Ali et al., 2014).

Refer children to a dental practitioner who will decide if treatment is necessary.

Hypodontia refers to a condition where a tooth or teeth fails to form, this tooth or teeth are then termed to be congenitally missing. While it may not cause immediate issues if a deciduous tooth fails to form, it can mean the corresponding permanent tooth will also fail to form (Letra A, et al 2021). Untreated hypodontia in permanent teeth can result in crowding or misalignment of the teeth, multiple missing teeth can present with many issues such as deteriorating jawbone density, difficulty chewing, unclear speech. Often, many missing teeth or oliogodontia is indicative of a genetic syndromic /condition.

Refer children to a dental practitioner who will decide if treatment is necessary.

These teeth develop in the correct position but are abnormally small, narrow, and conical in shape. While smaller teeth are not usually a cause for concern, the corresponding permanent teeth may also be affected. The upper lateral incisors are most commonly involved, though other teeth can be affected. Treatment is usually for cosmetic purposes and, when relevant, to support orthodontic alignment of the permanent dentition.

Natal teeth are those teeth which present either at birth, or during the first 30 days of life. Despite the technical distinction both are commonly referred to as natal teeth, due to their similar presentation and clinical implications.

These early erupting teeth are relatively rare, occurring in approximately 1 in 2000–3000 births (Adekoya-Sofowora 2008). The vast majority are mandibular incisors and if a child presents with posterior natal teeth it must be investigated as it may be related other systemic conditions or syndromes (Harrison, Cameron, & Widmer, 2022).

Management depends on how stable the tooth is and the effect it has on both the infant and the mother. Teeth that are secure and not causing any symptoms may be left in place and monitored by an oral health professional. However, if a natal tooth is loose, there is a risk it could be inhaled, so referral to dental practitioner for removal is strongly advised. Removal may also be necessary if the tooth interferes with feeding, such as by causing discomfort to the mother during breastfeeding or irritating the baby’s mouth.

Importantly, taking out natal or neonatal teeth does not affect the future development or eruption of the child’s permanent teeth.

2.8 Teething

Teething refers to the eruption of the deciduous teeth. A child may feel discomfort as new deciduous teeth emerge, usually from about six months of age onwards.

Signs of teething may include:

- irritability

- a child placing objects or fingers in their mouth and biting on them

- increased dribbling

- swelling of gums

Teething is not associated with fever or diarrhea, and these symptoms should present to a GP or other suitable health professional.

Do not recommend:

- Amber necklaces: There is no evidence that these alleviate teething pain, and they introduce a choking hazard.

- Teething gels: There is evidence that improper use can result in rare but serious and even fatal consequences.

Refer to ‘Section 7.5’ for more information about teething gels

Advice for parents: temporary relief from teething discomfort

- Give the child something to bite on, such as a cold (but not frozen) teething ring, cold wet face cloth, toothbrush or, if they already use one, a dummy.

- Give the child something firm to suck on, like a sugar-free rusk.

- A child may be more likely to accept soft food at this time as it requires less chewing.

- Gently rub the child’s gums with a clean finger.

- Provide soft food at meal times

Refer to section ‘Section 7- Medication and oral health’ for more information about medications to ease teething pain

Eruption cysts

During teething, some children may develop fluid-filled sacs known as eruption cysts. These cysts are typically harmless and usually resolve as the tooth erupts through the gum. If they persist more than a couple of weeks refer to a dental professional as there are more serious but very rare conditions that present similar.

Refer to ‘Section 6.5 -Eruption Cysts' for more information

Dribbling

Dribbling can help develop a baby’s salivary glands, preparing them for solid foods or easing teething pain. However, it’s important to note that finger-sucking and dribbling are normal parts of development and don’t always indicate teething. If dribbling seems excessive, a referral to a speech therapist might be necessary.

2.9 Tooth grinding

Babies can sometimes rub their gums together especially when new teeth are starting to erupt.

Many children grind their teeth at some stage. Some children just clench their jaws quite firmly, while others might rub their teeth against each other so hard that it makes a noise. Some children grind their teeth during sleep. Often, they don’t wake up when they do it.

Most of the time, teeth grinding does not damage a child’s teeth and is temporary. Sometimes teeth grinding can cause flat or polished areas on the biting surface called wear facets.

Teeth grinding in infants and toddlers, and occasional teeth grinding in older children, does not require any intervention. However, if a child is experiencing headaches, tooth pain, jaw joint dysfunction or is wearing down the teeth, this should be discussed with an oral health professional (Mindell & Owens 2010). Devices to protect teeth (known as night guards or dental splints) can help and are available from oral health professionals for older children and adults.

Tooth grinding can be a sign of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) or sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), especially if combined with snoring or mouth breathing. It is recommended children who grind their teeth be referred to their GP to screen for SDB or OSA.

2.10 Thumb and finger sucking, lip sucking, and dummies (Non-nutritive sucking)

Finger, thumb or dummy sucking are common childhood non-nutritive sucking behaviours. Parents may be concerned that these habits will affect their child’s dental development.

Sucking is a natural reflex in babies and young children and sucking a thumb, finger or dummy can be a self-soothing behaviour. Tired, stressed or hungry children may suck their thumb, fingers, or dummy.

Most children grow out of sucking habits between two and four years of age.

The dental effects of sucking habits are usually reversible up until the age of six or seven, because children still have their deciduous teeth. If sucking habits occurs beyond the age of six or seven, when permanent teeth are erupting, changes to the growth pattern can make these permanent.

Dental problems may arise including:

- Buck teeth – excessive sucking can push the front teeth out of alignment, causing teeth to protrude. This can alter shape of the face and lead to an open bite.

- Open bite - a misalignment of the teeth where the upper and lower teeth do not meet when the jaws are closed.

- A lisp – a child who sucks their fingers and thumbs can push their teeth out of their normal position. This interferes with the correct formation of certain speech sounds resulting in a lisp.

- A narrow palate and crossbite - excessive sucking can restrict lateral growth of the maxilla resulting in a V shaped arch instead of a U shape. This results in crowding of the teeth and may result in mouth breathing, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) or sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).

Lip sucking

Sucking of the lower lip may occur in isolation or it may occur with thumb sucking. When the lower lip is repeatedly held beneath the upper front teeth the result is usually an open bite. An open bite is a type of misalignment where the upper and lower teeth do not meet when the mouth is closed, leaving a gap that can affect chewing, speech, and overall dental alignment.

Tips for helping children break sucking habits:

- Help the child understand: It’s important for children to understand the habit and be willing to stop.

- Reward positive behaviour: Praise or use a reward system like stars on a calendar. Reward periods can gradually be extended.

- Offer encouragement: Family members can provide support.

- Avoid nagging: Let the child control the habit. Occasional, light-hearted reminders can be more effective than constant repetition.

- Provide reminders: Consider using a mitten, bandaid, or nail paint as a reminder not to suck. It is important these are not used as punishment but as a reminder.

- Distract the child: Engage them in active play or provide toys to keep their hands busy during screen time or car rides.

Information for families can be found: Thumb sucking | Better Health Channel